David Bowie - Blackstar in the night sky

A personal tribute I wrote five years ago, the day after his death.

[Orignally published on January 12, 2016] David Bowie had never been closer to my life than in recent years. His influence had always been there – I don’t think there are many creatives who’ll say otherwise – but always more in the background, even if it loomed larger than I often realised. “And Bowie, of course,” you’d say when discussing influences. “Of course,” was the reply.

He became active rather than passive again that morning in 2013. People began muttering online about a new Bowie album that had appeared on iTunes. The Next Day. It had to be a joke. Well, it was in a way – him playing a joke on the world, again – but it was also true.

Recently, m’learned colleague Jo Callis wanted our band Fingerhalo to play a few Bowie songs for a birthday bash. He selected some Ziggy-era material for us. We went, “Och, aye, that’s easy.” It wasn’t easy at all. It felt easy. It played easy. But the process of trying to inject some of that genuine feel, along with our own expressions as musicians (otherwise it would be a note-perfect copycat performance, and who wants that?) took far more energy than anyone, except Jo, realised it would.

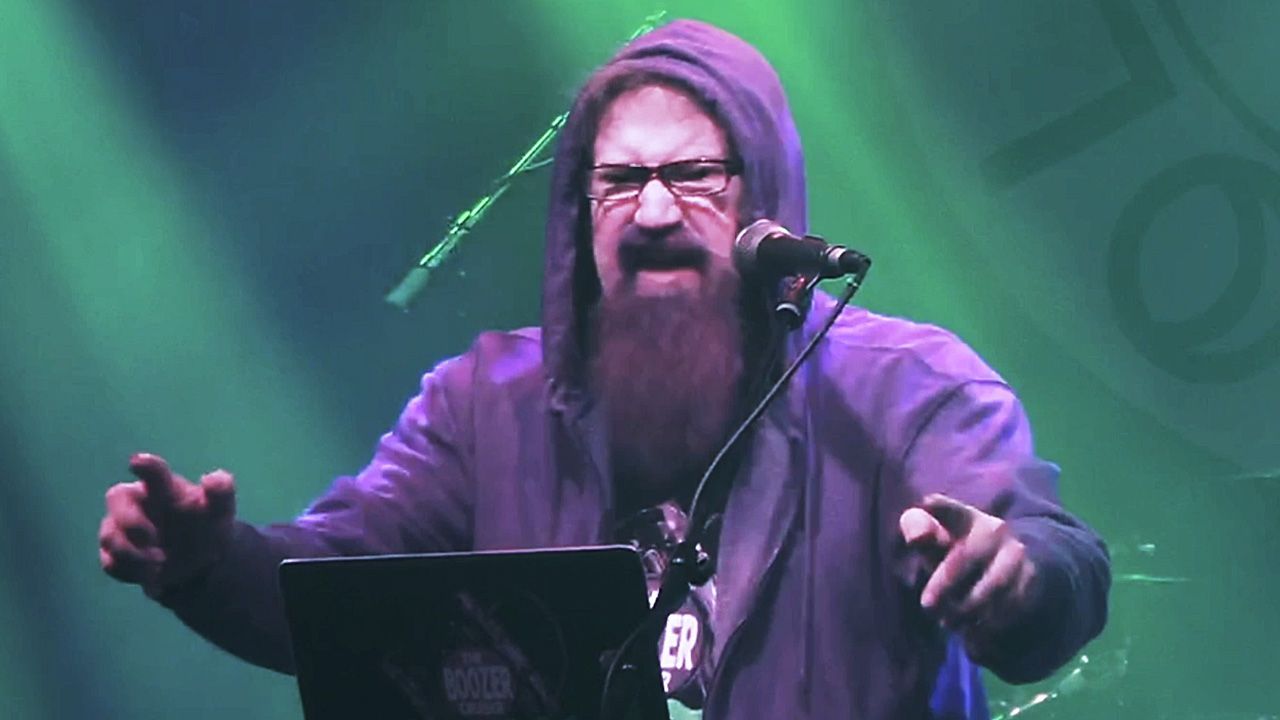

So it was with some sense of trepidation that we played a wee set in Edinburgh’s Citrus Club last week (January 8). Those songs – Supermen, John I’m Only Dancing, Ziggy Stardust, Width Of A Circle (oh yes!), Hang On To Yourself and Where Have All The Good Times Gone (by the Kinks, covered by Bowie) – all have lives of their own that are very much more complex than one might realise at first. Just like people with lives of their own.

I think it’s fair to say we’d all like another bash at doing them justice. But the experience of playing Bowie songs live, and experiencing their lives, was a far deeper one than I’d realised it would be.

I was already impressed by Blackstar, the album released just before his death. I’d been writing around and about it for months, obviously. But when I saw the title track video I felt a sense of real joy – for the creation, for the expression, and once again, for the sense of fun that dripped through something that clearly had a darker side. There’s a scene during the section that’s almost a tribute to his 70s and 80s work, where he thumbs his nose at the camera. That summed up the entire piece to me. Still does.

Then, of course, he died. My last interaction with him was publishing his Lazarus video last week. For various reasons I hadn’t got round to watching it properly, but I’d been fascinated by the concept that there were two Bowies going in difference directions in the promo. Now we know what that was about, sadly.

Monday was the first day of my Christmas holiday, since I’d worked throughout the end of December – and of course the death of Motorhead icon Lemmy had been an emotional drain, as well as a series of long shifts at the keyboard. I was still processing the experience of that, and of having played Bowie songs on stage the previous Friday… and of having marked the beginning of my break by staying out far too late and drinking far too much Guinness and whisky.

The entire day, of course, was scunnered. I already had an appointment to shoot a feature for STV Glasgow about the late Gerry Rafferty. Soon I had several requests to talk about Bowie for various news channels – I wound up doing five separate interviews, and the last one was on a TV chat show, by which time I was truly fried.

Just as the floor manager announced ten seconds to going live, the responsibility of the situation hit me. I had my own personal reaction to Bowie’s death, of course. But in a few moments I was going to have to speak on behalf of a lot of people who couldn’t find their own words, and speak on behalf of an artistic – and human – legacy that was far beyond words. And it was the fifth time that day I’d have done it.

I managed it because it’s my job. Same way, as a young whippersnapper, I managed to remain at my newspaper post during the Dunblane massacre, the death of Princess Diana, the Gulf Wars and other events where your training takes over to prevent you breaking down with the weight of emotion.

I managed for long enough because it’s my job. Then I realised that I wasn’t going to manage for much longer. I’d been asked to stay for the end-of-show chat, when the chef serves up dinner-for-a-tenner and the hosts conduct a less structured interview. I knew I couldn’t.

Instead, I bolted out of the studio as quickly as politeness allows. Outside was a wet, dark and imposing cityscape – a bit like the Ziggy Stardust cover art – and I was grateful to hide in it.

I crossed the Squinty Bridge and along the bank of the Clyde, and stopped at the location where most of the action in my novella There’s No’ Been A Murder takes place. It felt like a different world from when I’d last visited. But then, I realised, I’d become a different person since then.

Leading up to the Bowie concert I’d spoken to a few people about how the general sense of excitement drops when you get older. As a youngster you’re energised by the thought of doing something new, and of how it will change you. Later, when you’re all been-there-done-that, you’re pretty certain you know who you’ll be afterwards, and that it’ll be an incremental change rather than a monumental one. A lot of the energy remains, but that additional spark isn’t there.

Well, Bowie showed me. He showed me when the songs really did take on a life of their own, such that it was much more difficult to control them than any of the band had realised it would be. He showed me when the hints I’d taken from Lazarus proved to be much more imposing than I’d realised. He showed me when my reaction to his death was far more attenuated than my reaction to Lemmy’s death, since it entered my life in a completely different manner.

I couldn’t put that into words as I stood in the rain on the Broomielaw. It occurred to me that every single shimmer on the surface of the water, as it came out from the shadow of the Kingston Bridge, was a Bowie idea we’d never get to know about. It wasn’t just the sky that was crying by that point.

His widow Iman had already put it into words for me, although I only read them last night: “Sometimes you will never know the true value of a moment until it becomes a memory.”

She’s right, so she is. I’ve had a bastard of a year and I’ve struggled to keep a sense of energy about my work. Just after I had the affrontery to blame the way of the world and the ravages of time for that, Bowie touched my life like he’d never done before, giving me an experience as wide and deep as the Clyde, and with more ideas packed inside than I’ll manage to express in a lifetime of continued storytelling.

And there he is, thumbing his nose at me for the rest of forever, and I’ll spend my share of that (I hope) exploring the true value of the moments he just gave me, as they become memories.

And that, you see, is why in a very real sense David Bowie is still alive – and so are many, many, many others who influence us.

(Fingerhalo had been planning to record a version of John I'm Only Dancing, and we rushed into action after hearing of Bowie's death. We scraped together a rapid-response concept for a video and we were all very proud of how it came out.)